Todays electrical infrastructures depend on sophisticated methods of energy management and safety that go far beyond simple wires and fuses. As demands grow, so do the expectations for reliability, speed, and accuracy in delivering electrical energy to every load. From automotive and aerospace, understanding advanced distribution concepts is essential for designing and maintaining systems that operate reliably under all conditions.

At its essence, power distribution is the discipline of channeling energy from a single source to multiple destinations without excessive loss or imbalance. Traditional systems relied on electromechanical devices to manage power. While effective in older systems, these methods struggle when facing microprocessor-controlled devices. To meet new operational standards, engineers now employ electronic circuit breakers, digital fuses and smart sensors, and adaptive electronic protection that adjust continuously to load variations.

An electronic fuse (e-fuse) performs the same protective role as a conventional one but with precision control. Instead of melting metal, it detects and isolates faults electronically, often within fractions of a millisecond. Many e-fuses reset automatically after the fault clears, eliminating manual replacement. Advanced versions also communicate diagnostics via industrial communication buses, sharing real-time current, voltage, and event logs for deeper insight.

semiconductor-based relays have replaced electromechanical relays in many industrial and vehicular applications. They switch faster, create minimal EMI, and suffer no mechanical wear. In environments subject to shock and harsh conditions, solid-state components outperform mechanical types. However, they introduce thermal challenges, since semiconductors generate heat under heavy load. Engineers mitigate this through heat sinks, derating, and thermal shutdown.

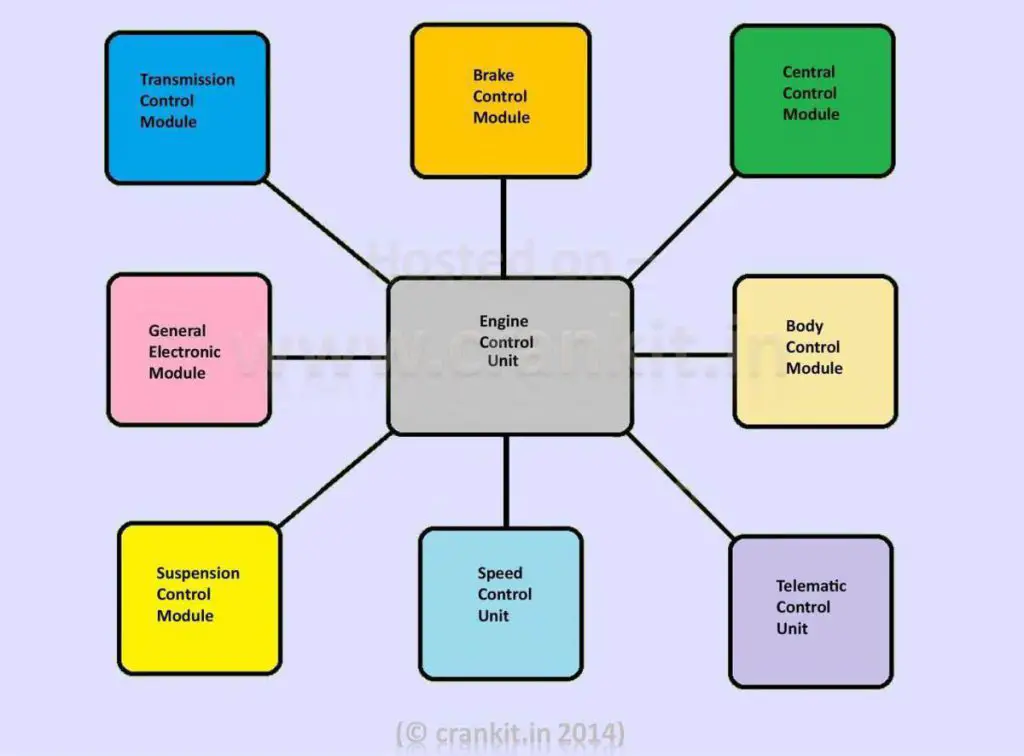

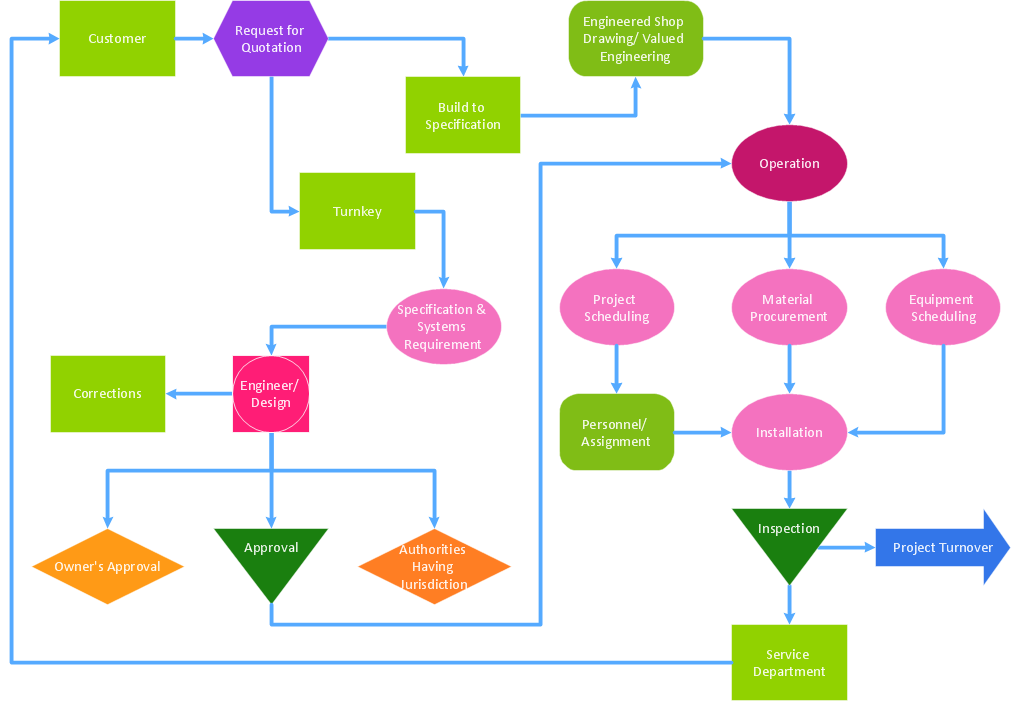

A well-structured power distribution architecture separates main, auxiliary, and control subsystems. Main feeders use busbars or heavy cables, branching into localized subnets protected by distributed e-fuse modules. Each node balances between safety and uptime: too tolerant and faults persist; too strict, and false trips occur. Smart systems use self-adjusting trip curves that distinguish legitimate loads from anomalies.

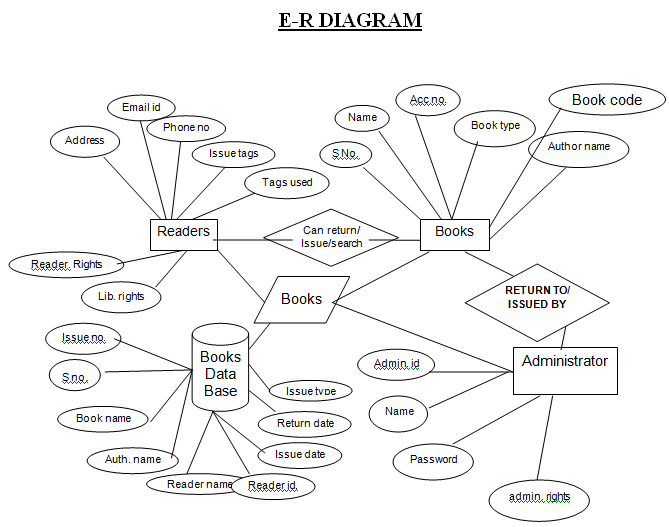

Grounding and return-path design form the invisible backbone of modern power networks. Multiple groundssignal, power, and chassismust coexist harmoniously. Poor grounding causes noise, voltage drift, or false readings. To prevent this, engineers implement star or single-point grounding, using low-impedance connections that maintain stability under vibration. ECUs and monitors now monitor ground integrity in real time to detect early degradation or corrosion.

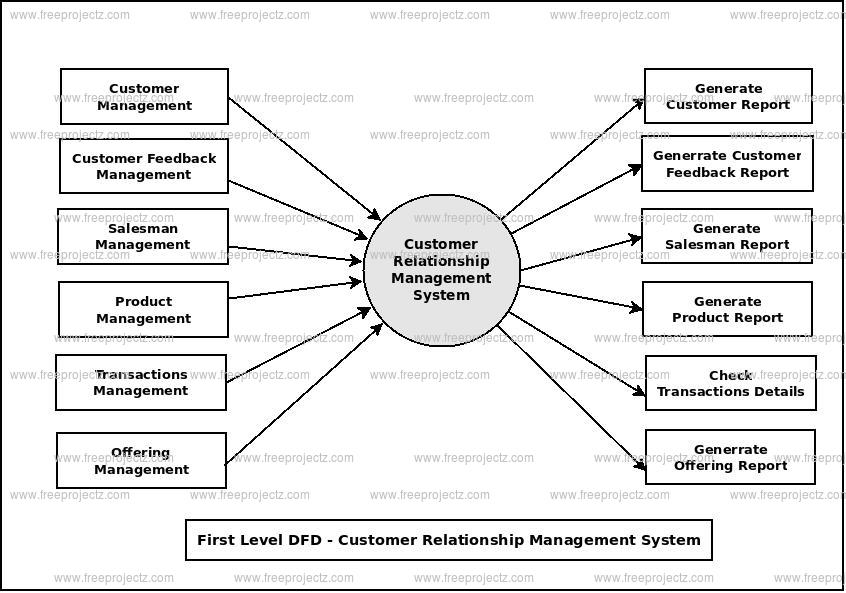

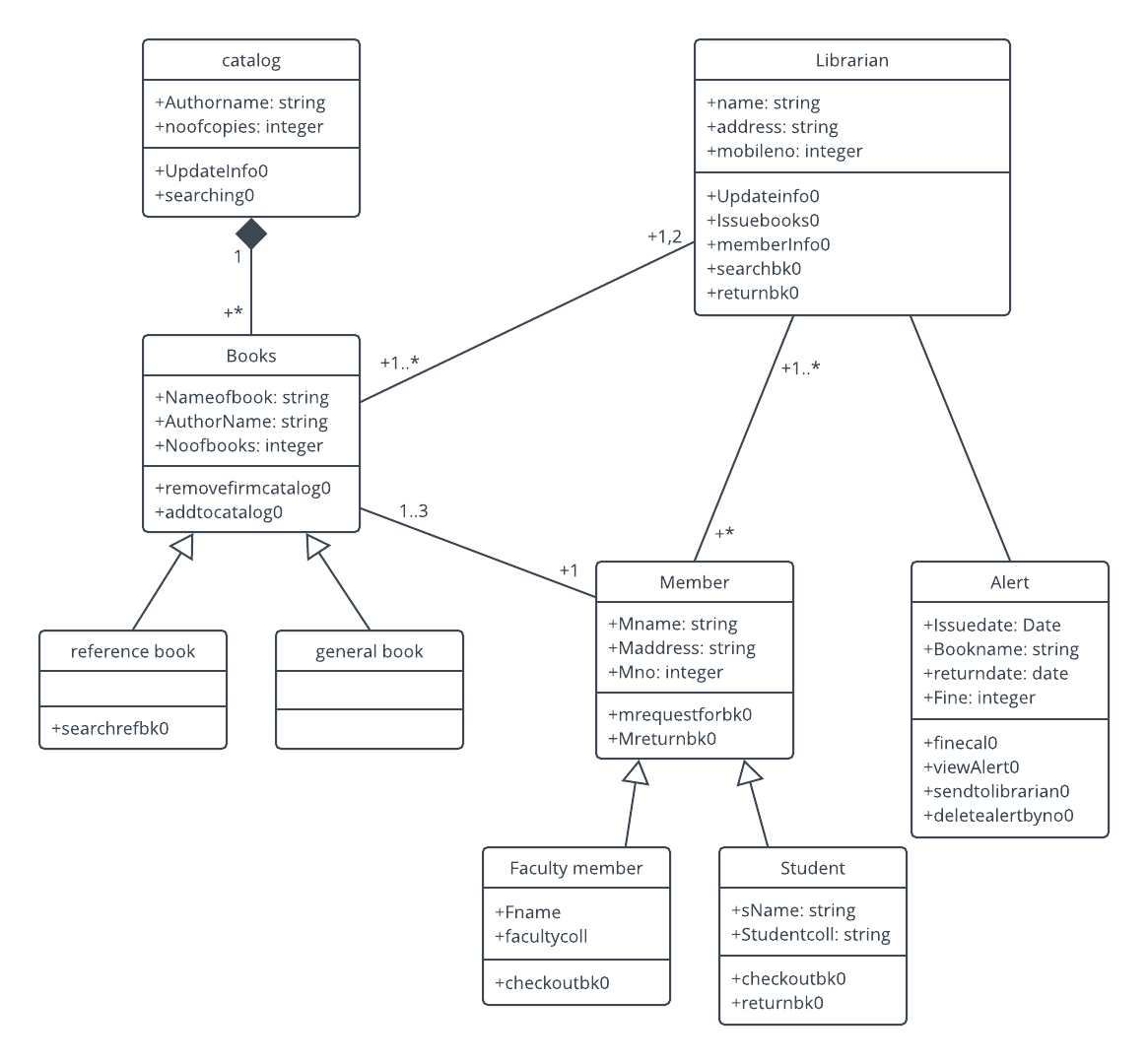

The integration of digital power management marks a major shift in energy control. Microcontrollers within PDMs and switchboards measure real-time loads, log data, and control logic distribution. This intelligence enables data-driven reliability, where systems detect circuits nearing overload. Supervisory software visualizes current paths, fuse status, and system health across entire installations.

Protection components themselves have evolved. In addition to e-fuses, engineers employ polyfuses (PTC resettable fuses) and magnetic-trip protection. Polyfuses increase resistance as they heat, resetting automatically after coolingideal for space-constrained electronics. Current-limiting breakers trip fast enough to cap energy before conductors overheat. Selection depends on load type and criticality.

Modern simulation tools enable engineers to simulate current paths and protection timing before hardware is built. By analyzing electrical and thermal interactions, they ensure cables operate within ampacity limits. These digital models lead to predictable, safe systems.

From a maintenance view, smart distribution simplifies troubleshooting and monitoring. Built-in sensors and logs record overcurrent events, pinpoint which circuit tripped, and allow remote resets via software. This is invaluable in vehicles, aircraft, and offshore systems, reducing manual intervention.

Despite new technologies, the principles remain timeless: power distribution is still about directing current with precision. Whether through busbars or MOSFET arrays, each design must protect the circuit, contain failures fast, and maintain traceable schematics.

In the bigger picture, advanced distribution and modern fusing techniques represent the future of electrical safety. They show how hardware and firmware now combine to form adaptive systems that are not only protected but also self-aware and self-correcting. Through these innovations, engineers achieve both performance and protection, ensuring that energy continues to power the world with precision.