In every modern control system, input and output elements form the essential bridge between the real environment and electronic logic. They convert real-world phenomenatemperature, pressure, movement, light, or substance concentrationinto signals that controllers can analyze and act upon. Without this conversion, automation would be ineffective and unresponsive. Understanding how these devices operate, and how they communicate, is crucial for anyone building or maintaining modern automation systems.

A measuring device is a device that detects a physical quantity and transforms it into an electrical signal. Depending on the application, this could be frequency output. Behind this simple idea lies a sophisticated signal conversion process. For example, a temperature sensor may use a RTD element whose resistance changes with heat, a strain transducer may rely on a strain gauge that deforms under load, and an photoelectric element may use a photodiode reacting to light intensity. Each of these transducers turns physical behavior into usable electrical information.

Sensors are often divided into powered and self-generating types. Powered sensors require an external supply voltage to produce an output, while self-powered sensors generate their own signal using the energy of the measured variable. The difference affects circuit design: active sensors require regulated power and noise suppression, while passive types need signal conditioning for stable readings.

The performance of a sensor depends on accuracy, resolution, and response time. Engineers use amplifiers and filters to refine raw data before they reach the controller. Proper grounding and shielding are also essentialjust a few millivolts of interference can produce false measurements in high-sensitivity systems.

While sensors provide input, drivers perform output work. They are the muscles of automation, converting electrical commands into movement, heat, or pressure changes. Common examples include electric motors, electromagnetic plungers, valves, and heating elements. When the control system detects a deviation from target, it sends corrective commands to actuators to restore balance. The speed and precision of that response defines system stability.

Actuators may be electromagnetic, hydraulic, or pneumatic depending on the required force. DC and AC motors dominate due to their precise response and easy integration with electronic circuits. incremental drives and servomotors offer precise positioning, while linear actuators convert rotation into push-pull movement. In high-power systems, electromagnetic switches serve as intermediate actuators, switching large currents with minimal control effort.

The interaction between detection and control forms a closed control system. The controller continuously reads sensor data, evaluates deviation, and modifies response accordingly. This process defines feedback automation, the foundation of modern mechatronicsfrom simple thermostats to advanced process control. When the sensor detects that the system has reached the desired condition, the controller reduces actuator output; if conditions drift, the loop automatically compensates.

In advanced applications, both sensors and actuators communicate via digital networks such as Profibus, EtherCAT, or CANopen. These protocols enable synchronized communication, built-in fault detection, and even remote parameterization. intelligent sensing modules now include microcontrollers to preprocess signals, detect faults, and transmit only meaningful datareducing communication load and improving reliability.

Integration also introduces technical complexities, especially in timing and accuracy management. If a sensor drifts or an actuator lags, the entire control loop can become unstable. Regular calibration using known values ensures data integrity, while actuator verification keeps motion consistent with command. Many systems now include auto-calibration routines that adjust parameters automatically to maintain accuracy.

Safety and redundancy remain essential. In mission-critical environments, multiple sensors may monitor the same variable while paired actuators operate in parallel. The controller validates data to prevent erroneous actions. This approachknown as fault-tolerant designensures that even if one component fails, the system continues operating safely.

From simple switches to advanced MEMS devices, sensing technology has evolved from passive elements to intelligent components. Actuators too have advanced, now including position feedback and current monitoring. This fusion of sensing and action has transformed machines from reactive systems into adaptive, self-regulating platforms.

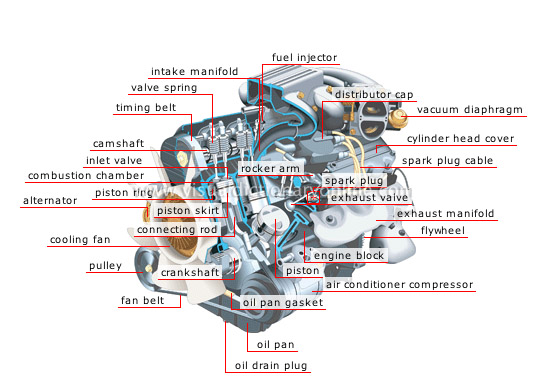

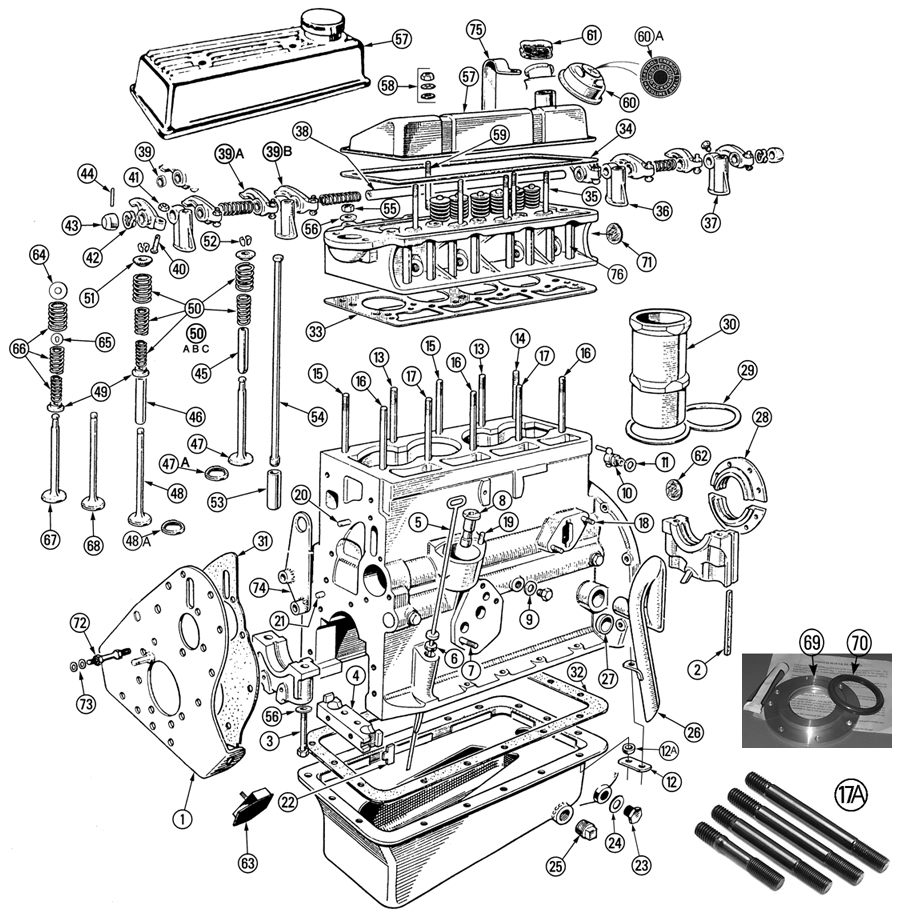

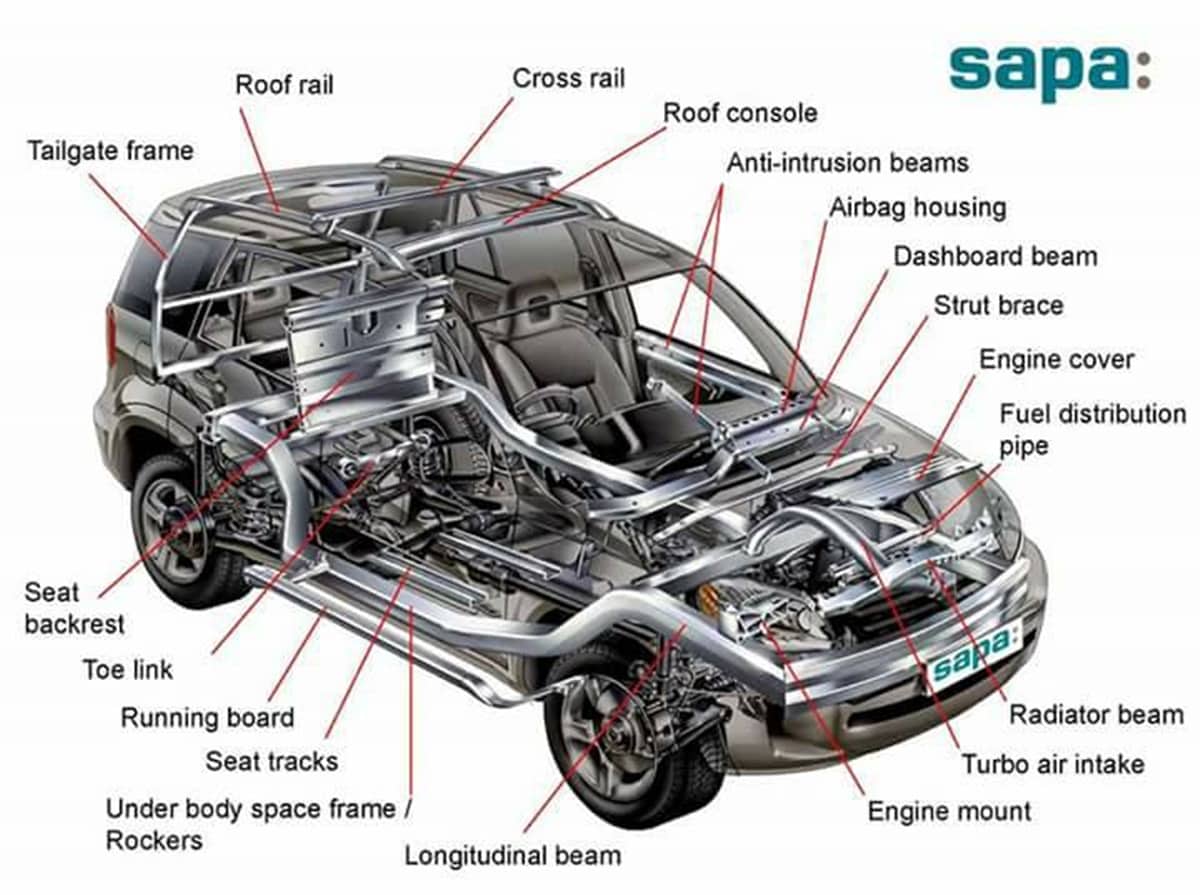

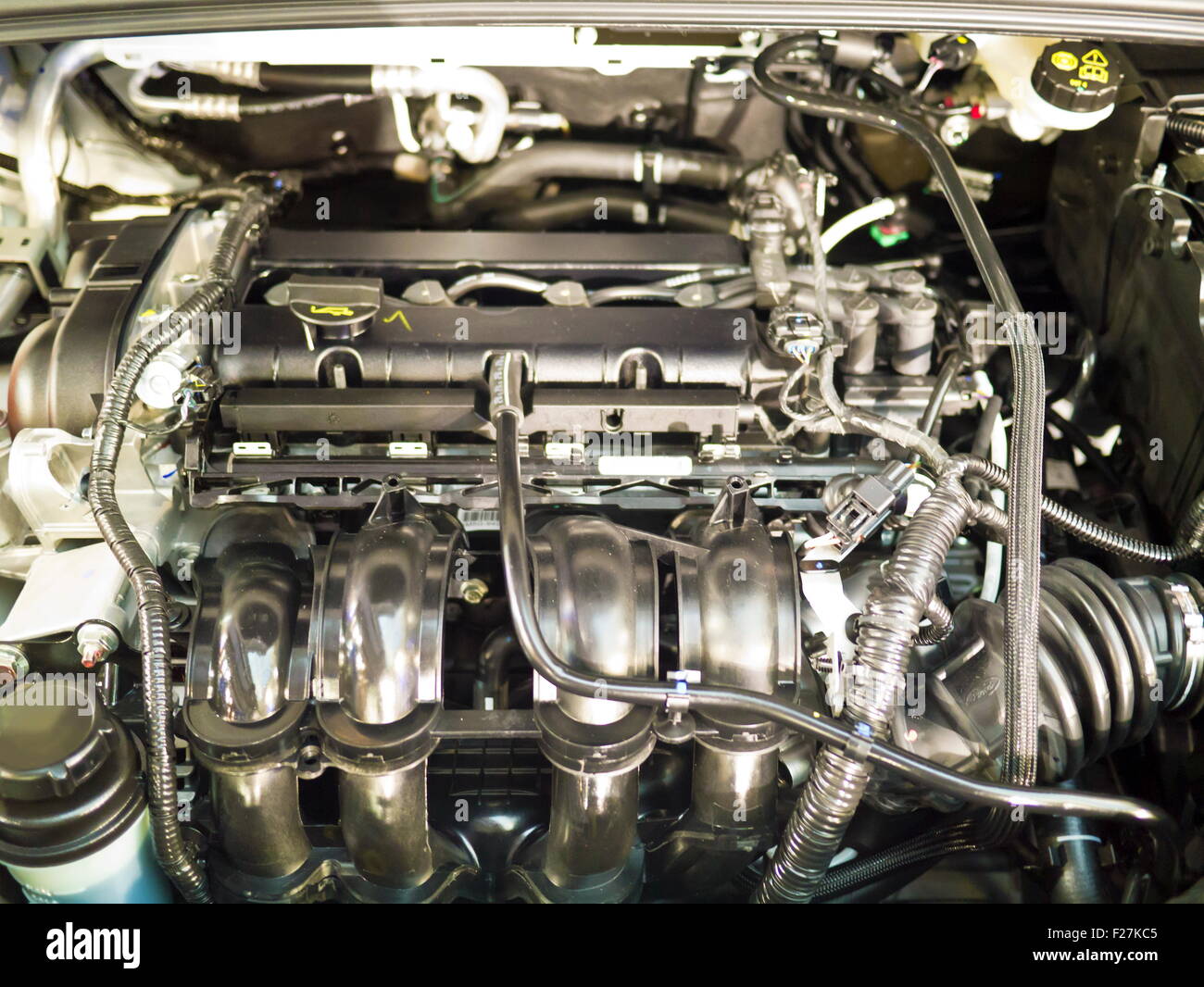

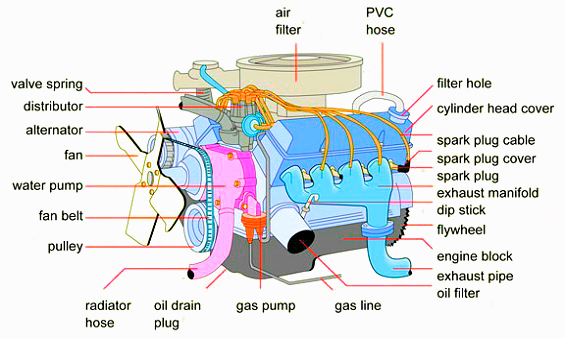

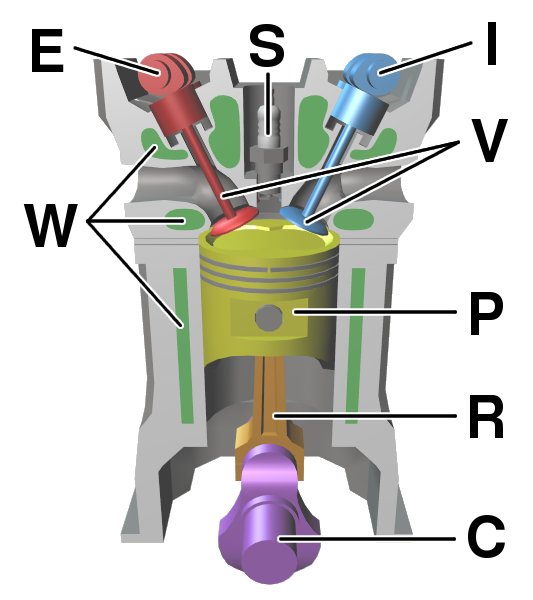

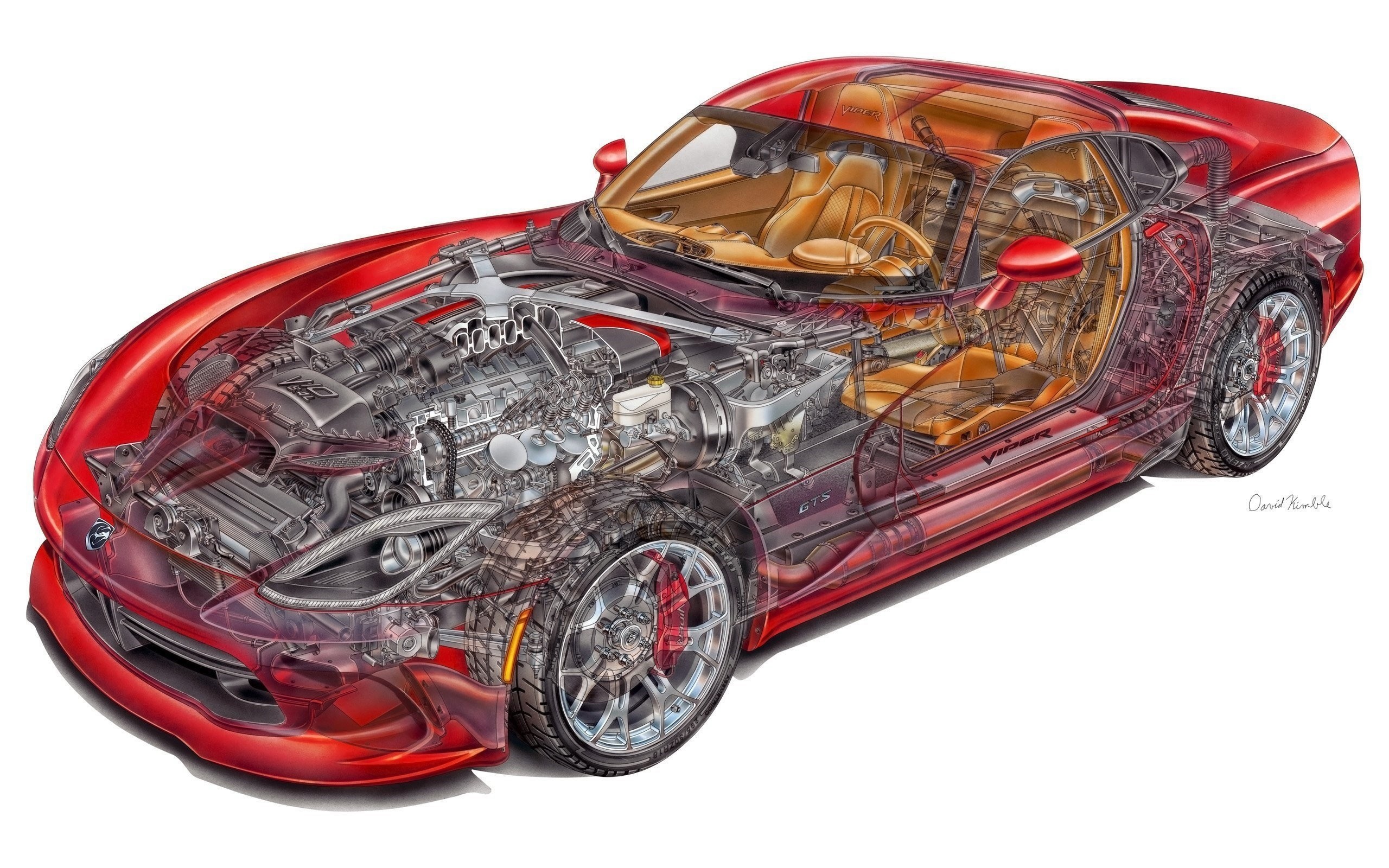

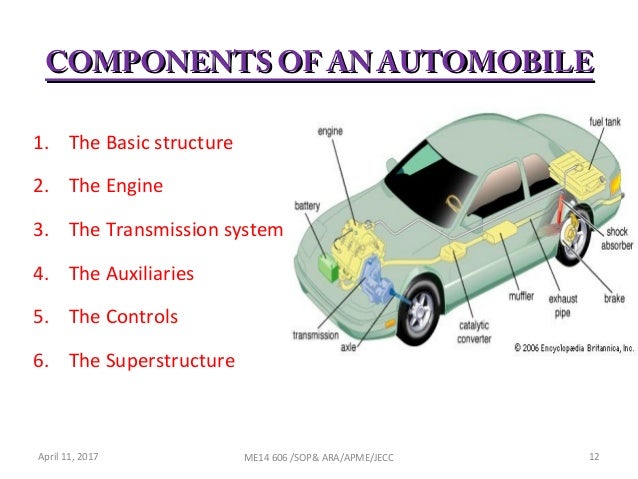

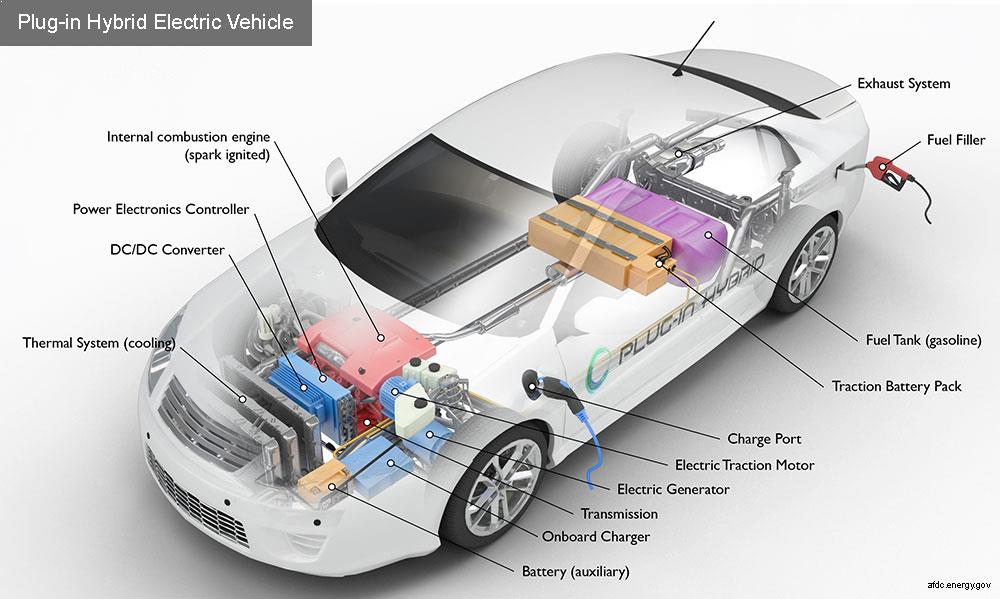

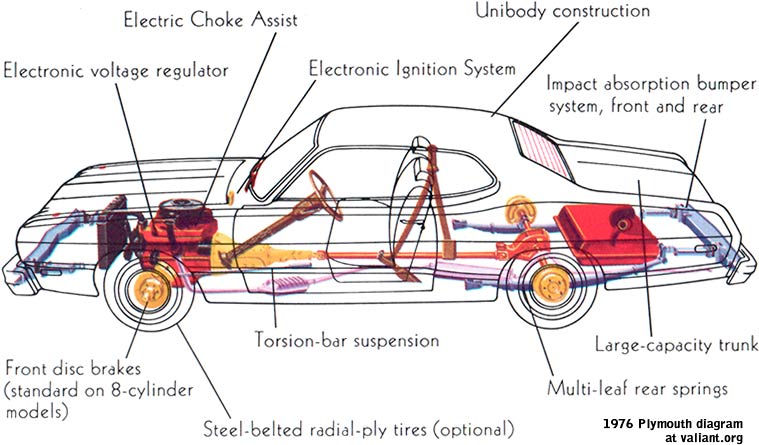

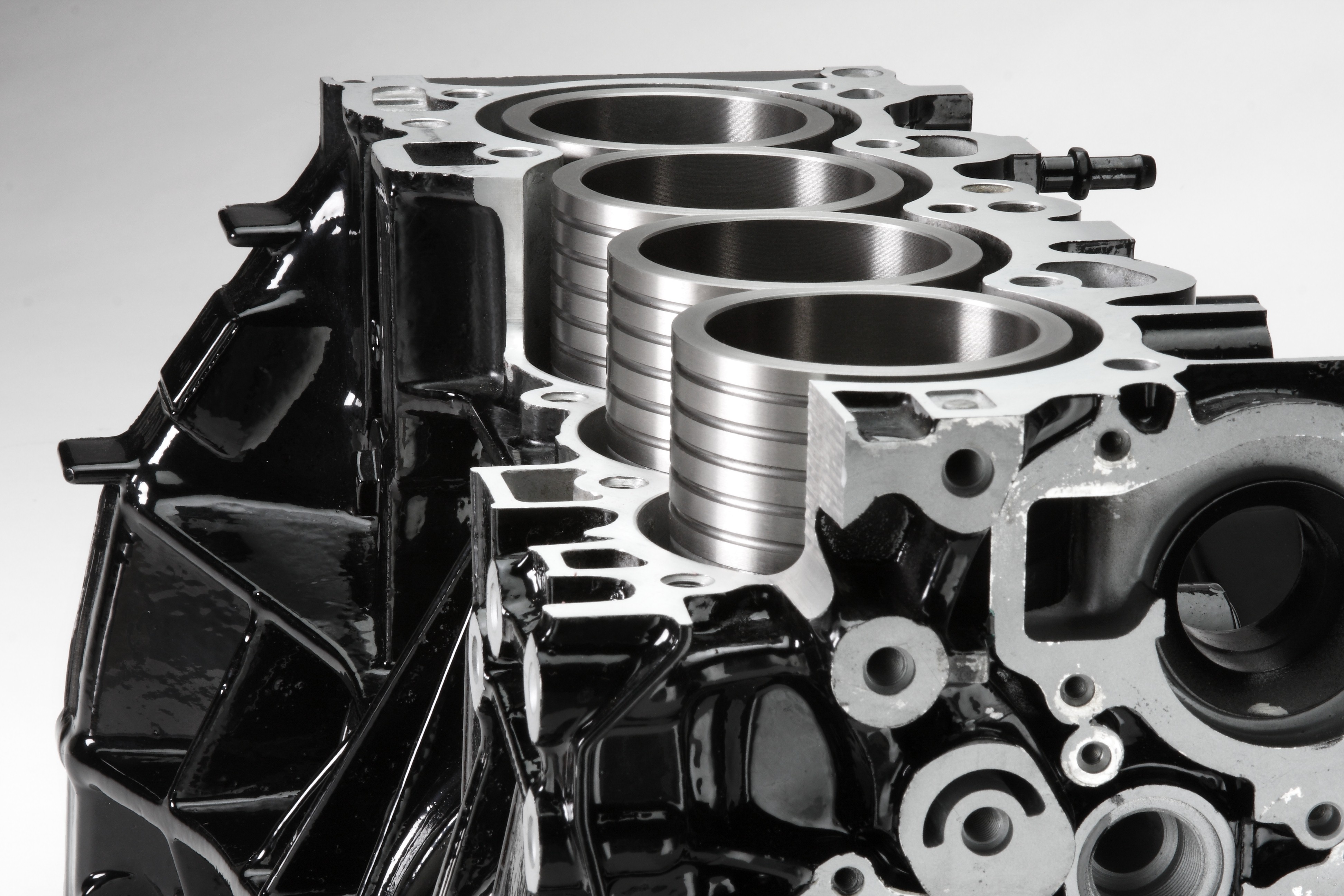

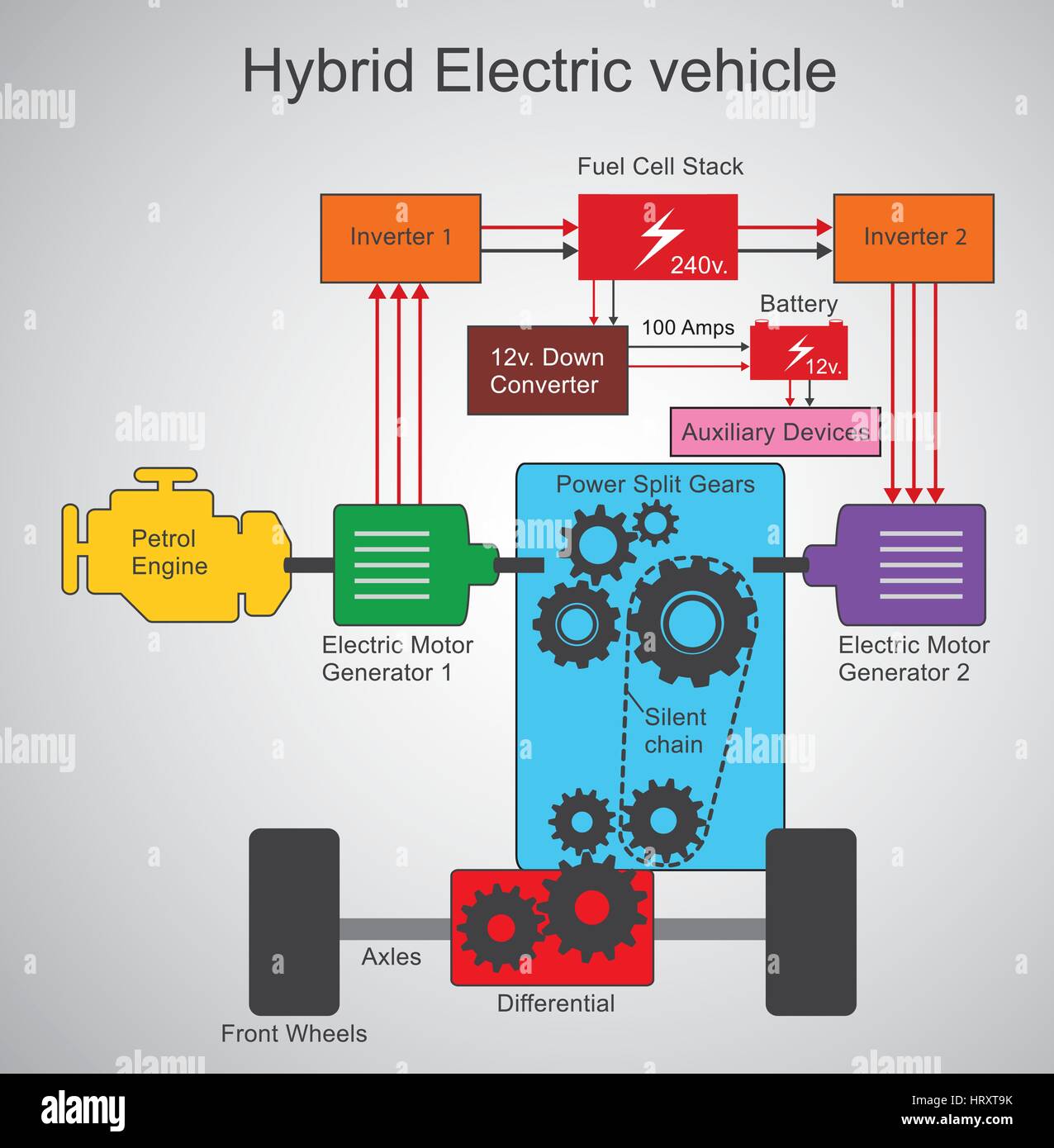

Ultimately, the partnership between sensors and actuators defines the capability of any control system. Sensors perceive reality, actuators enforce change. Between them lies the controllerthe brain that interprets, decides, and commands. When all three work in harmony, the result is a machine that can think, move, and adapt. That is the essence of modern automation and the theme explored throughout Diagramatic Structure Of A Vehicle Engine (Vehicle Engine, 2026, http://mydiagram.online, https://http://mydiagram.online/diagramatic-structure-of-a-vehicle-engine/MYDIAGRAM.ONLINE).